Japanese Settlement in San Juan, Bolivia: Educational Fair

The other day, we held an educational event for people who live in San Juan.

We wanted people to think about the way children spend their time at home so the theme for this event was “learn with as a family” and had 9 different booths where you could experience cooking, science experiments, environmental studies, and hair styling.

On the actual day, not only Nikkei people but many Bolivian people came so we were glad many people were able to enjoy our fair.

I was in charge of the Japanese booth. The goal of this booth was for Bolivians to learn about Japan and out culture so I decided to write people’s names in Japanese, and while playing bull’s eye learning how to greet someone in Japanese.

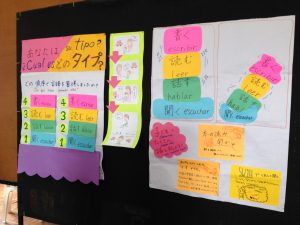

For Nikkei people, I asked them to place a post-it to “Colonia” words they knew and did a presentation about language acquisition. The goal of this was so we could discuss the presented topics.

Firstly, about the “Colonia” language. Colonia (colony, settlement in Spanish) language is the language made and spoken in the settlements. It’s mainly made up by combining Japanese and Spanish words or combining the nuances of both languages. These are some examples:

“Cambiakko” = cambiar (Spanish word for “exchange”) + koukan-kko (slightly childish way of saying “exchange” in Japanese)

“Sembraki” = sembrar (Spanish for “to plant”) + kikai (Japanese for machine), this is the word they use for a seed planting machine

“Pato-uchi” = pato (Spanish for duck) + uchi (Japanese for “to shoot”)

“Seco Seco” = seco (Spanish for dry) + the Japanese way of saying onomatopes

And finally, they say “genchi-jin” (Japanese for “locals”) when they talk about Bolivians. It’s mostly used by the elderly.

Colonia language is fascinating isn´t it? Some people couldn’t come up with examples, but I think I will continue investigating more about it.

A Nikkei lady in her 20s mentioned how some nouns and verbs became part of their Spanish but since it’s slightly disrespectful she said she had to be careful when talking to elders. Most of the people in San Juan are originally from Kyushu (the southwestern most of the Japanese islands) so how the way they conjugated some words resembled the dialect from Kyushu. It might be interesting to look further into it!

Next, the exhibition on natural language acquisition. I got a lot of advice from Professor Fujita-Round when making the poster, thank you very much.

In this section, I wanted to discuss about how we can prevent from children thinking that learning Japanese is “studying”, by trying to explain basic concepts on naturally mastering a language. (Eventually, I explained mistakes foreigners make when learning Japanese, and common mistakes students in San Juan make).

The people I talked to learned Japanese in the order of “hearing-speaking-reading-writing”. It was the same with Spanish. Many people mentioned that their children learnt Spanish by playing with someone who spoke Spanish.

However, after the “listening phase”, the way children learnt differed. For example, some learnt it naturally by talking to their friends in Spanish, but for some it was not that easy and had to learn it by studying for exams after they entered school.

Some even said that it was a very stressful experience for them to get used to the Bolivian community and to learn Spanish after leaving the Nikkei settlements to go to high school. The reason they studied Spanish was only to get good grades in school. “Was it hard for me to learn Spanish because I didn’t follow the order?” some people questioned. It was very interesting learning that even if people lived in similar environments, they have different ways of perceiving the Spanish language.